Large Scale Graph Mining: Pregel

One of the things that has been keeping me busy lately was a paper I had to write for one of my classes about large-scale graph mining. It’s been a lot of work, but it’s been quite enlightening - I’ve learnt quite a bit. I will probably upload the paper to my site as well, once I’ve finished this seminar, but in the meantime I want to write a bit about Pregel, since I found it a really interesting concept.

Pregel is Google’s architecture for distributed computation of a variety of values pertaining to graphs and to a certain extent represents their successor to the widely popular MapReduce framework. In contrast to MapReduce it’s designed for a more specific task and also differs quite a bit with regard to its implementation. The parallelization occurs on a far lower level and unlike the reduce stage of MapReduce, data and results typically stay local for the duration of the execution.

It essentially operates on the same principle as multi-agent systems, with each node of the graph representing its own autonomous agent with local data and behavior rules. These node agents are distributed across a typically large number of computers and use message passing to communicate between each other when necessary. To avoid race conditions and deadlocks, communication is not performed at arbitrary times, but rather in globally synchronized fixed intervals called supersteps. Between communication phases, the individual nodes execute their computations completely asynchronously without access to external data (neither reads nor writes). During the computation phase, nodes may enqueue any number of messages to be sent to other nodes, however due to the iterative nature of the execution, these messages will only be available to their target nodes at the next superstep.

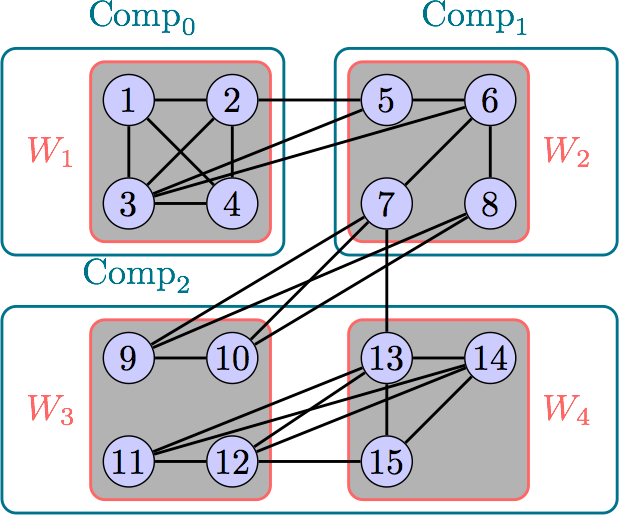

Schematic of a small Pregel Network. Multiple workers can run on the same machine for better load balancing.

Pregel is written in C++ and contains all the necessary code to distribute data

across different workers, monitor worker health and roll back to backups when

necessary, facilitate communication, and provide analytics to the user. To

implement an algorithm for Pregel, all the user must do is inherit from the

Vertex class and override its compute function. How to write this function

is however not so straightforward. Many existing graph algorithms rely on access

to global data throughout the execution, and writing a Pregel implementation

that sends data from every node to every other node in each step would thoroughly

saturate the I/O bottleneck and defeat the purpose of the decentralized

computing. Instead, typical applications have vertices sending messages only to

their neighbors, which for most sparse graphs derived from real world data is a

small number.

So far this is quite theoretical, and the reader may be wondering how limited-scope agents can be used to achieve the desired global behavior. For this we first have to look at what exactly a node is capable of doing. In fact, a node is capable of doing very little, possessing only a few methods and properties. In pseudo-code, a vertex looks more or less like this:

class Vertex:

function compute(received_messages)

function vote_to_halt()

function send_message_to(destination, message)

var value;

var out_edges;

bool active;

const var superstep;

As mentioned previously, the compute method is what the user must override for

their specific application and it is passed an iterable containing the incoming

messages at each step, and may call the other methods and modify the instance

variables. The vote_to_halt method is already implemented by the parent class,

and simply changes the instance’s active attribute to False, which means that in

subsequent supersteps the node will do nothing unless reactivated by incoming

messages. Also already implemented is send_message_to, although users can

specify arbitrary data types for the message itself. Similar to messages, the

attribute value can also be user defined depending on the application, and

represents some form of local storage. The out_edges property is set

externally at initialization and contains a list of edges connected to the node

(in the shape of target ID and weight pairs) and can be changed during runtime.

The active property indicates whether the node has voted to halt and is

accessible globally: when all nodes have voted to halt, execution terminates.

Finally superstep is provided externally and basically represents a global

clock signal.

So, given that one can really only customize the method compute, and the data types for method and value, the programming paradigm must change significantly from traditional algorithms. To illustrate this shift, here is an example of how to implement single source shortest path (SSSP):

value: integer, initalized to INF for all nodes except the source, which starts with 0message: integercompute: the following (rather Python-like) pseudocode:

compute(received_messages):

minimum_distance = min(received_messages)

if minimum_distance < value:

value = minimum_distance

for destination, weight in out_edges:

send_message_to(destination, value + weight)

vote_to_halt()

When every vertex has voted to halt, their values will be either the shortest

path to the source, or INF for unreachable nodes. Total number of supersteps is

the diameter of the graph, and at each step a vertex sends at most

len(out_edges) messages, though often none at all if its value hasn’t been

updated since the last send. To my knowledge this is typical of the amount of

messages that need to be sent in a Pregel run, and indicates that computing a

global result can be achieved without very large exchanges of information.

Nonetheless, it is common knowledge that I/O operations are orders of magnitude slower than computations and especially so when performed over the network (when you consider that even writes/reads from SSDs are typically bottlenecks) so there are a certain number of optimizations implemented in Pregel to reduce the cost of communication. For starters, although each node can send messages to any other node, which may all be on disparate machines, each worker processes the messages enqueued during a superstep by its contained nodes and groups them by target location to send in a single bulk message.

Another bandwidth saving measure is the option to combine messages before sending them, according to a user-specified combiner function. This combiner function must be manually enabled and implemented depending on the algorithm, as Pregel cannot automatically determine a suitable combiner. In the case of SSSP, a combiner would look like:

combine(destination, messages_for_same_destination):

return destination, min(messages_for_same_destination)

According to Google, use of combiners reduces bandwidth use by a factor of four in practice. One key question that I have not addressed at all so far is: how does a worker know which machine to send messages intended for a certain vertex to? How are the vertices distributed across the machines in the first place? The answer to this is disappointingly primitive: each node has a unique ID, and a hash function of this ID is modulo’ed with the number of workers to obtain the index of which machine to place the node on. This same hash and modulo determine where to send messages during execution. This means that graph structure is not considered at all in the distribution of vertices and a clique of strongly connected nodes may wind up on different computers (or even different continents on the scale that Google operates on) and communication between them must be performed over network.

That really made me wonder how this naive solution can be the best option they came up with and how it can be that it doesn’t cause severe bottlenecking by the communication phases. To investigate this for myself empirically, I set out to recreate Pregel by myself (I know that there are open source versions such as Giraph freely available for anybody to download, but I didn’t do this for two reasons: 1. I wanted to get a better understanding of the inner workings and 2. I don’t actually have a server cluster).

So, being a simulation and not designed for high performance, I made it in Python (ergo: sequentially) since it’s easy to use; and since I wanted introspection, I made a graphical representation of the system state in Qt5 (simply because that’s what I know and I didn’t want to worry about learning something new). The project ended up getting surprisingly big, so I decided I might as well put it on github. The code should probably still get cleaned up a bit, and since nobody downloads software anymore these days, I want to look into making it a web-app (yay, web 2.0 :/) as well. I’ll go into more detail about this simulation and the insights gleaned from it in a future post. `